Why do people vote for bad candidates? In some cases, they may be electing the lesser of evils. But there are many instances where voters clearly prefer bad politicians. In a recent article on the political situation in Argentina, the Financial Times makes this observation:

“A year ago Larreta was well out front as the opposition candidate,” Germano said. But while praised for efficient management of Buenos Aires, critics say Larreta lacks charisma and struggles to connect with ordinary Argentines.

I rarely see “charisma” cited as an important attribute for politicians in places like Switzerland, Denmark or Singapore. It does seem to be important in places like Argentina, Brazil and the Philippines. Why? Shouldn’t voters prefer boring but honest technocrats that will tirelessly work in the public interest? Why the attraction to “lovable rogues”?

Think about the field of law. It seems to me that having a lot of charisma is more useful for a criminal defense attorney than for a judge. We want our attorney to be a passionate advocate for our cause. We’d like a judge to be a dispassionate arbiter of disputes.

Now consider the field of politics. Perhaps voters in highly successful places would prefer boring but competent administrators that will preserve the country’s good qualities. In less successful places, voters might prefer highly charismatic leaders that will fight for their faction against the “bad guys”. If I’m right, then the FT article might lead readers to think, “Hmm, if that’s what Argentine voters want, perhaps I should not invest in Argentina.”

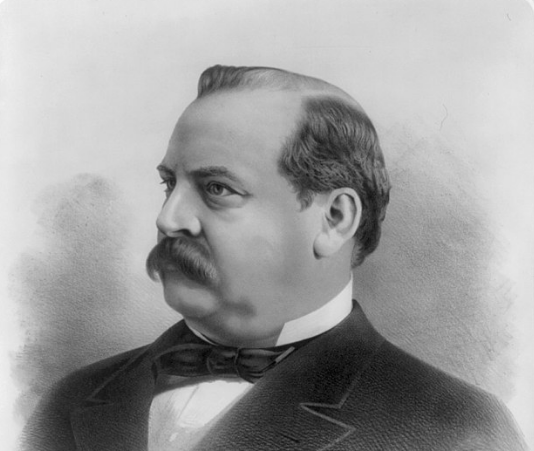

I am currently reading a new book by Troy Senik that makes a strong case for Grover Cleveland being the most unselfish man ever to serve as president of the US. But is that what we want? Here’s Senik:

Grover Cleveland was precisely the kind of self-made, scrupulously honest man that Americans often say they want as their president. We had him for eight years. And somehow, we forgot him.”

One argument is that while personal qualities might be nice, what really matters is the candidate’s views on the issues. I’m not willing to accept that as a complete explanation. It might apply to a general election, but their are far too many examples of primary races where the clearly inferior candidate wins out over the superior candidate despite having almost identical views on the key issues. (Why did Georgia primary voters opt for Herschel Walker over alternative GOP candidates?)

Here’s a question for people that are knowledgeable about American history. I know that George Washington is one of our greatest presidents. (He’s also one of my favorites.) But how would Washington rate if he had not led America to independence from Britain, and if he had not been America’s first president? What if his domestic and foreign policy achievements had been roughly comparable, but he served as president in the 1820s, or the 1880s? Might he be rated comparably to Cleveland, Coolidge, and other presidents that had personal integrity but boring administrations?

Washington and Coolidge were among the very few presidents that walked away from the presidency despite clearly being able to win another term. Senik makes a strong case that Cleveland had an amazing devotion to public service; often doing things that hurt him both personally and professionally because he thought it was the right decision. But that sort of unselfish devotion to the public interest is rare in a successful politician.

It seems likely that the qualities we’d like to see in a leader vary with the situation. For most of human history, people were organized into small groups, often fighting with neighboring tribes. I suspect that the qualities that would be useful for a Viking leader might be different from the qualities useful in a highly complex and affluent market economy such as Singapore. Because most of human history was more like the Viking world than 21st century Singapore, we may be hardwired to prefer the wrong kind of leader for the modern world.

It’s obvious to me that voters in less successful countries are often choosing leaders that make their country worse off. Less obvious is whether these leaders are making the voter’s particular faction worse off. Should voters prefer a “fighter” that will strongly advocate for their cause? How does the calculus change if that leader is also personally corrupt, and enriches himself with money and power at the public expense?

Fighting is often a negative sum game, and hence successful societies will often opt for boring leaders that cooperate rather than fight. That’s basically the rationale behind the European Union. But when voters are frustrated and angry, they’ll opt for charismatic politicians that are seen as being willing to fight against the other side.

So how does Argentina get out of this trap? How do they get to the position where a Grover Cleveland can successfully run for president of their country? I don’t know. Does the culture have to change first? If they somehow get richer, will that make voters opt for more sensible candidates? I suspect there are no simple answers. Society is a highly complex system, and change can occur from many different directions.

It is also possible that a society might go into reverse. It might become increasingly polarized and begin electing inferior leaders that are seen as “fighters”. Recently, I’ve read a number of articles making the case that classical liberals are too nice, and that rather than politely follow the rules we need leaders that will destroy the other side. (Grover Cleveland was a classical liberal, indeed the last small government Democrat to serve as president.)

I also wonder if charisma is a more important attribute for voters that favor an activist government. Perhaps voters believe that in order to enact lots of new programs, you need a charismatic politician that can persuade a majority of legislators. Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson both had strong personalities and an activist agenda. Cleveland was boring but lacked an expansive view of the role of government. Senik (p. 104) quotes him as saying:

“the people have a right to demand that no more money should be taken from them, directly or indirectly, for public uses than is necessary for [an honest and economical administration of public affairs.]. Indeed, the right of the government to exact tribute from the citizens is limited to its actual necessities, and every cent taken from the people beyond that required for their protection by the government is no better than robbery.”

PS. My wife and I recently began planning a long trip to Argentina. I’d already purchased an Argentine guidebook when I found out that the monetary system in Argentina is completely screwed up, which makes things very difficult for tourists. Now we are leaning toward Chile.

PPS. Happy Thanksgiving!

"politic" - Google News

November 25, 2022 at 03:58AM

https://ift.tt/govzmXC

The mystery of politics - Econlib

"politic" - Google News

https://ift.tt/4CFLIiA

https://ift.tt/g02chNq

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/bostonglobe/VNG7YMZTRWJ5WBFTJ5NVETPCQI.jpg)

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Subscribe Subscribe

Not your account?

View Comments

Join the Conversation

Please follow our comment guidelines, stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.